Table Of Content

Similarly, it is possible that temporal contiguity plays a more important role in conditioning for young learners, as compared to older ones. It is possible that the MTL procedure was more efficient because in this procedure the time interval between the natural discriminative stimulus and the programmed consequence was shorter, or more contiguous, than for LTM prompting. In MTL prompting, when the participant responded correctly to the most intrusive prompt level, the consequence was delivered immediately. With LTM prompting, often the least intrusive prompt was ineffective and a few prompts were delivered before the child responded correctly, leading to more time between the discriminative stimulus and correct response and reinforcement. If trials were terminated upon the delivery of an incorrect response at a given prompt level and followed by a new trial where a more or less intrusive prompt was delivered with 0 time delay, both MTL and LTM prompting would be equated in terms of reinforcement immediacy. Designs such as ABCABC and ABCBCA can be very useful when a researcher wants to examine the effects of two interventions.

Interaction effects in multielement designs: inevitable, desirable, and ignorable.

Lang and colleagues (2011) used an ATD to examine the effects of language of instruction on correct responding and inappropriate behavior (tongue clicks) with a student with autism from a Spanish-speaking family. To ensure that the conditions were equivalent, all aspects of the teaching sessions except for the independent variable (language of instruction) were held constant. Specifically, the same teacher, materials, task demands, reinforcers, and reinforcer schedules were used in both the English and Spanish sessions. The independent variable (in this case, the token reinforcement system with the increasing dB criterion) was actively manipulated by the researchers, and the dependent variable was measured systematically over time. Each phase included a minimum of three data points (but not the five points required to meet the standards fully), and the number of phases with different criteria far exceeded the minimum three required. Although many behaviors would be expected to return to pre-intervention levels when the conditions change, others would not.

Within-subjects designs: To use or not to use?

The change in reinforcers was applied to all prompting conditions at the same point in time for this participant. Conventional approaches to single-subject data analysis rely on visual inspection (as reviewed earlier in this article). From the perspective of clinical significance, supporting a “visual inspection–only” approach is warranted because the practitioner (and, ultimately, the field of practice) is interested in identifying only those variables that lead to large, unambiguous changes in behavior. One argument against the exclusive reliance on visual inspection is that it is prone to Type 1 errors (inferring an effect when there is none), particularly if the effects are small to medium (Franklin, Gorman, Beasley, & Allison, 1996; Todman & Dugard, 2001). Evidence for experimental control is not always as compelling from a visual analysis perspective. In many cases, the clinical significance of behavior change between conditions is less clear and, therefore, is open to interpretation.

Additional information

The second “A” phase acts as both the withdrawal condition for the ABA portion of the experiment and the baseline phase for the ACAC portion. This design is ideal in situations where an ABA or ABAB study was planned but the effects of the intervention were not as sizable as had been hoped. Under these conditions, the intervention can be modified, or another intervention selected, and the effects of the new intervention can be demonstrated. The design has the same advantages and disadvantages of basic withdrawal designs but allows for a comparison of effects for two different treatments.

Recent Developments in Group-Sequential Designs

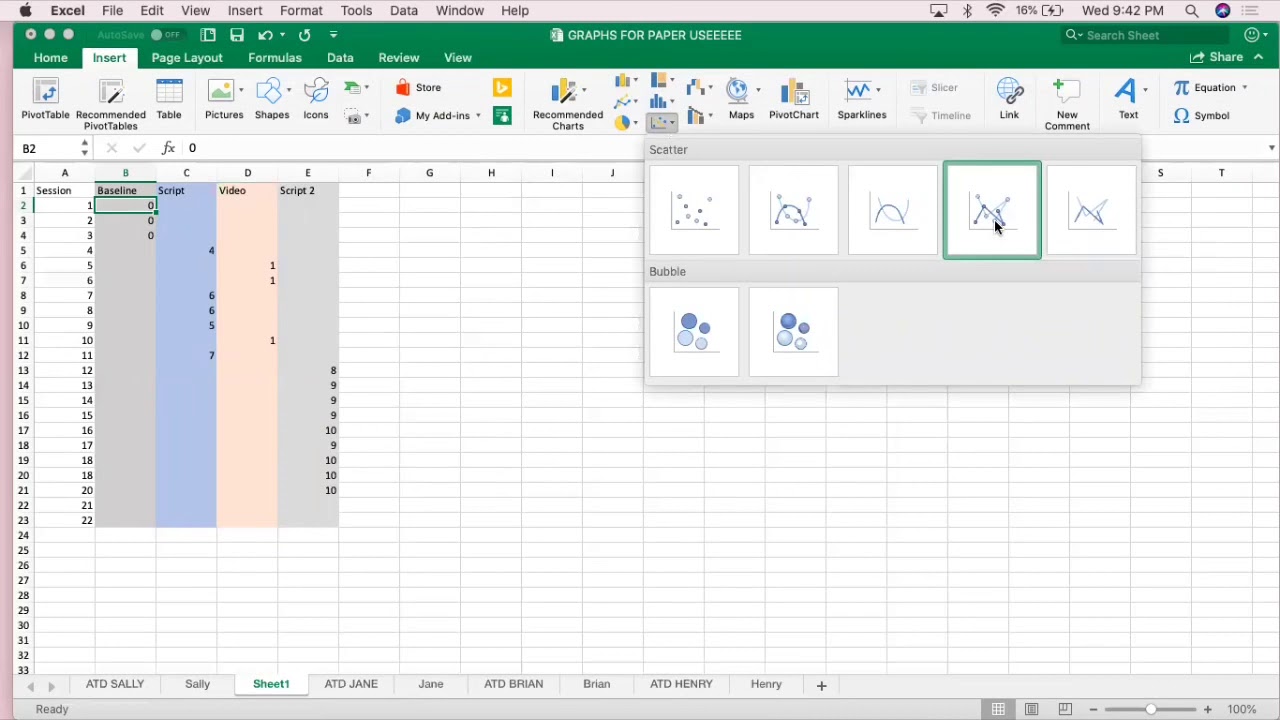

For instance, only stating that counterbalancing was used (e.g., Russell & Reinecke, 2019; Thirumanickam et al., 2018) is often not sufficient to understand and replicate the procedure. Regarding ATDs with block randomization, the most straightforward option is to use this label for the design, or the term “randomized block design” (e.g., Sjolie et al., 2016) and/or to describe the procedure clearly. For example, Lloyd et al. (2018) in particular refer to random assignment between successive pairs of observation, whereas Fletcher et al. (2010) somewhat more ambiguously state that the interventions were administered “semi-randomly” to counterbalance which treatment takes place first each data.

Seven alternative designs for the new Notre-Dame spire - Dezeen

Seven alternative designs for the new Notre-Dame spire.

Posted: Thu, 25 Apr 2019 07:00:00 GMT [source]

However, a substantial limitation arises when ADISO is used for ATD data with restricted randomization because the analyst would have to decide exactly how to segment the alternation sequence (i.e., which comparisons to perform). With different segmentations, the quantification of the difference between conditions can lead to different results. The recommendation is to segment the sequence in such a way that it allows for the maximum number of possible comparisons (e.g., segment AABBABBAABBA as AABB-AB-BA-AB-BA and not as AAB-BA-BBAA-BBA). In cases where different segmentations lead to the same number of comparisons (e.g., BAABAABABABB can be segmented as BAA-BA-AB-AB-ABB and BA-AB-AAB-AB-ABB), a sensitivity analysis comparing the results across different segmentations is warranted. In the remaining sections of this manuscript, the emphasis is placed on data analysis options for ATD data.

This study identified effective prompt topographies during the prompt topography assessment and then compared prompt hierarchies using only effective prompt topographies. Under these conditions, all three preschool-aged children diagnosed with ASD mastered target responses with the MTL prompting hierarchy and did not master target responses with the LTM hierarchy, even with 20 % additional sessions. A paired-stimulus preference assessment (Fisher et al. 1992) was conducted to identify preferred edible items. During subsequent sessions, the three items identified as most preferred were provided by the interventionist contingent on correct prompted and independent responding. At the beginning of each experimental session, the participant was asked to choose one of the three preferred items and that item was used for the remainder of the session. The interventionist conducted a second preference assessment for activities (e.g., iPad) with Sean during the prompt hierarchy comparison phase, because Sean’s teacher independently chose to restrict access to edibles throughout the day.

The Need for Quantifications Complementing Visual Analysis

The need for multiple conditions can make multiple-baseline/multiple-probe designs inappropriate when the intervention can be applied to only one individual, behavior, and setting. Also, potential generalization effects such as these must be considered and carefully controlled to minimize threats to internal validity when these designs are used. Nevertheless, multiple-baseline designs often are appealing to researchers and interventionists because they do not require the behavior to be reversible and do not require the withdrawal of an effective intervention. When selecting conditions for a multiple-baseline (or multiple-probe) design, it is important to consider both the independence and equivalence of the conditions.

Demonstration of experimental control is achieved by having differentiation between conditions, meaning that the data paths of the conditions do not overlap. Wacker and colleagues (1990) conducted dropout-type component analyses of functional communication training (FCT) procedures for three individuals with challenging behavior. The data presented in Figure 6 show the percentage of intervals with hand biting, prompts, and mands (signing) across functional analysis, treatment package, and component analysis phases. The functional analysis results indicated that the target behavior (hand biting) was maintained by access to tangibles as well as by escape from demands. By the end of the phase, the target behavior was eliminated, prompting had decreased, and signing had increased. To identify the active components of the treatment package, a dropout component analysis was conducted.

Ethical considerations regarding the withdrawal of the intervention and the reversibility of the behavior need to be taken into account before the study begins. Further extensions of the ABAB design logic to comparisons between two or more interventions are discussed later in this article. A description of the criteria developed by the panel as well as their application to evidence-based practice in CSD follows. 4For phase designs, several A-B comparisons can be represented on the same modified Brinley plot, because each A-B comparison is a single dot. However, for an ATD, there are multiple dots for each sequence (i.e., one dot for each block). Therefore, having several ATDs on the same modified Brinley plot can make the graphical representation more difficult to interpret.

This article is aimed at providing behavior analysts with additional data analytic options, using freely available web-based software. During the initial four sessions of the alternating treatments phase, responding remained at zero for all three word sets. Steadily increasing trends were observed in both of the directed rehearsal conditions beginning in the fifth session, whereas responding remained at zero in the control condition. The rate of acquisition in the directed rehearsal plus positive reinforcement condition was higher than in directed rehearsal alone throughout the alternating treatments phase. The latency in correct responding observed during the initial sessions of the alternating treatments was a demonstration of noneffect.

No comments:

Post a Comment